By Hannah Kubbins

Asst. Arts & Life Editor

Every angle, seat, person and space served a purpose in the Doane dance studio last weekend. Students, educators, Granville residents and their children filled the space in anticipation for All Sides in View, presented by the Department of Dance at Denison University.

Instead of the typical setup of a performance, with the performers on an elevated stage or in front of the spectators, those in attendance formed a square encompassing the dancefloor.

Chair of the department Sandra Mathern introduced the program and ended with a powerful quote that set the tone for the evening when she referenced John Cage, “We are not, in these dances and music saying something…We are rather doing something. The meaning of what we do is determined by each one who sees and hears it.”

The night began with Stafford Berry Jr.’s piece entitled “Colony (in progress).” The piece had three parts beginning with “Biology.” A spotlight focused on Nana Ichikawa ’18, slinking around on her back. Soon, other dancers were revealed to be imitating her movement. They all seemed to have a relationship with one another, but this relationship was never explicit.

“Biology” seemed very primitive and animalistic, but the dancers made these movements beautiful and natural.

“Politics and Place,” part two of Berry’s piece was more direct. The piece made a point to divide the dancers based on race, implying the politics of race in any given place. The dancers exited in these groups as well, the minority women leaving first with the white women following.

Berry’s piece accomplished many things, the most significant was the extreme diversity of the cast. All of the dancers had different bodies, races, ages, and movement styles.

Though very diverse, the cast was all female. When asked if this was intentional, Berry replied, “The cast is intentionally all female. While I typically work with all males in my professional company, I wanted to challenge myself to do the opposite with this endeavor.”

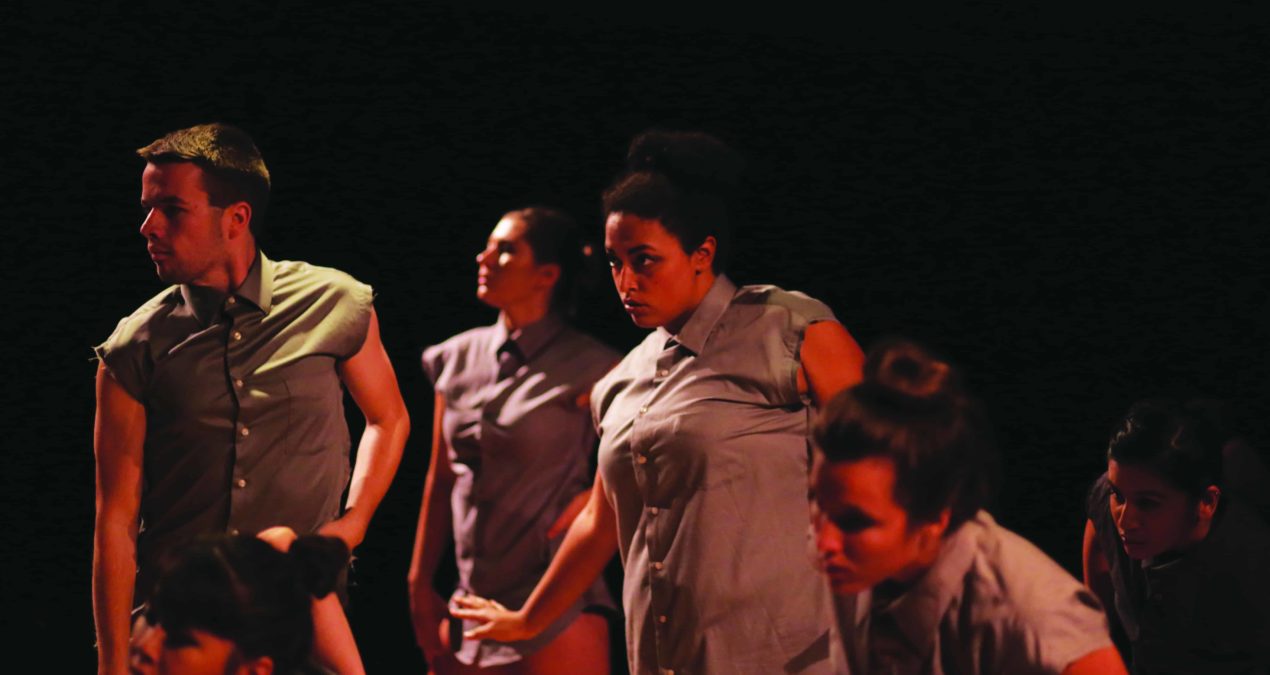

Visiting Assistant Professor Michael J. Morris’s piece, however, featured both male and female dancers.

Morris said that their “approach to making this dance was as a minimalist, formalist composition. There is no intended narrative, story, symbolism, or representation.

Rather, it is very much about these bodies performing these actions within this structure, as well as the broader social context in which these movement vocabularies circulated.”

Entitled “becoming becoming becoming,” Morris’s piece began with each dancer entering individually, imitating a fashion show. The whole first part of the piece was uniform from the way the dancers entered, to the clothes they wore, to the movements they performed.

With the dancers together, the movements resembled poses in a pin-up magazine.

Not to say the poses were trashy by any means, but it was clear the movements were supposed to capture what society deems as extreme femininity/sexuality.

Graciella Maiolatesi ’16, said how during these movements the dancers made eye contact with audience members. “It was clear the audience members were uncomfortable to return our eye contact. That was the point,” Maiolatesi states.

The piece continued, still addressing femininity, but in a different way. While the first portion held reference to the fashion/modeling world, the second portion was heavily embedded in ballet. Maiolatesi states that this part was in direct reference to Swan Lake.

The first and second phases of the piece presented the often discussed “Mary and Eve” binary of femininity. In other words, a female can only be one or the other: a good, quiet, obedient mother, or an evil, outspoken, deceitful seductress.

The final portion featured a crawling movement that is often associated with animals and insects. To get into this position, the dancers dropped to the floor, signifying a fall from grace, or falling from the extreme notion of femininity. Morris notes how this part of the piece is “we see where femininity tips over into the animal; it is a kind of ‘beyond.’”

Morris calls this final position, a kneeling position that requires every muscle to be clenched and still, “imperceptible.”

“This imperceptibility,” Morris says, “is where you recognize that something is taking place but it is something you cannot fully recognize or name, is perhaps also the excess of femininity, or even gender more broadly, where we cannot fully name or articulate what it is we are seeing.”

Personally, the piece overwhelmingly dealt with how we perform femininity and how the notion of being female society constructs is extremely unattainable.

Because it’s so unattainable, we often harm ourselves to try and fit the mold society makes for us.

Steering away from personal relationships, Mathern states that her piece, “Topographies,” focused on “the notion of an imaginary topography that influences the path and quality of travel, a journey across a landscape through which there are many obstacles.”

According to Mathern, the first section of her piece “imagines a topography of valleys and slopes, an environment that drives the dance, providing momentum, falling, and running in curving pathways.” This section was intended to give the sensation of “sweeping, suspending, rushing, and tumbling.”

Mathern noted how that the dancers were coached to feel the sensation of falling, risking the fall as far as possible before catching themselves in a run lunging into space, sliding into the floor or bounding into the air.

Mathern considered the body as a landscape to traverse on and around, which was clearly seen in the piece as a whole, but most evidently in a duet performed by Leah Edwards ’16 and Emily Farrow ’18. The two moved together beautifully, imitating movements and creating space between their bodies.

The pair flowed close together but would always leave space to maneuver around. The duet reflected Mathern’s statement about how her piece was meant to imitate “a shifting landscape that moves under our feet to which we must respond, or be in relation to.”

Though all distinct pieces, each piece created a connection with the viewers. Every member could hear the breathing of the dancers, see the expressions on their face, and feel the power of their movements.